“They had buried him under our elm tree, they said -- yet this was not totally true. For he really lay buried in my heart.”

Willie Morris, “My Dog Skip”

The snow came early to Maryland in 1994. October, for heaven’s sake, summer was barely over. For our 10-year-old son, Christopher, it was his very first one. Just three months earlier he had been swimming in the South China Sea, but his parents’ eight-year adventure as journalists in Hong Kong had come to an end, and now everything in his life was brand new.

We lived in a white house on a short street with a steep hill, so there was sledding to be done. Those snowmen weren’t going to build themselves, and later, there would be cocoa.

Although Christopher had never seen snow, he had read about real winters, and he knew his rights. There was a trickling creek at the bottom of our hill, and deer lived in the woods. Golden retrievers with red-checked bandanas ruled the neighborhood. Back home in America, and we all paraded home with expectations.

We knew for certain we wanted our son to go to a neighborhood public school. So far, his entire education had been at a private, Lutheran-run International School perched high above Hong Kong’s majestic Repulse Bay. It was time for him to shed his uniform, drop the daily church services before class, and enjoy an old-school education. Both Barbara and I had done the same, and it hadn’t hurt us.

During his first month at the elementary school in our leafy Bethesda neighborhood, his teacher gave a surprise geography quiz where one of the questions was, “What is the capital of Scandinavia?” Christopher was perplexed. He quietly crept to the front of the room and whispered to his teacher that Scandinavia was not a country, and therefore did not have a capital. Imagine her surprise. “Children, just skip Question Number Six…”

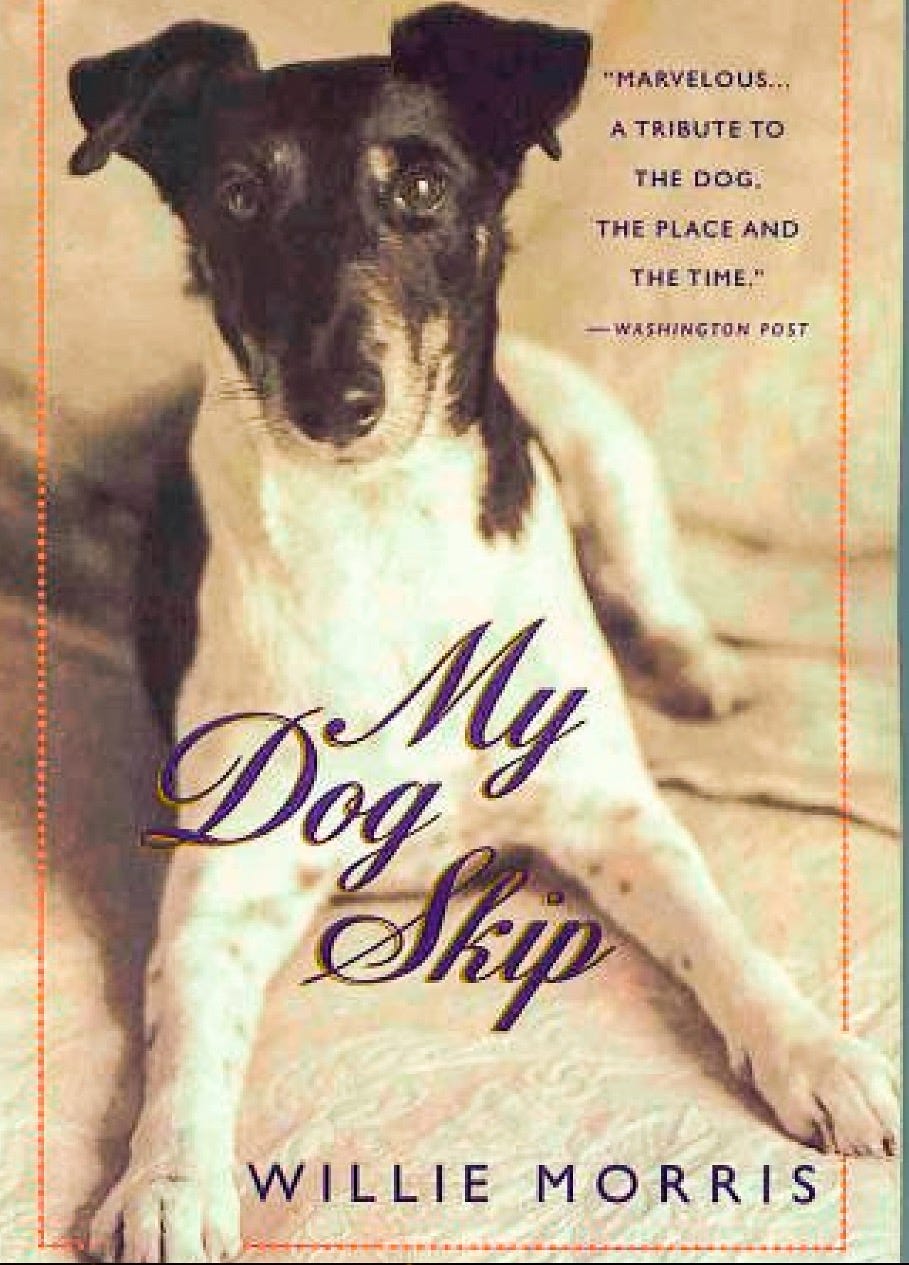

This and similar episodes made us wonder about the decision we had made, but Christopher insisted he was happy there. Later that school year his class read “My Dog Skip,” the poignant Mississippi memoir by the great Willie Morris, who wrote of his childhood in Yazoo City, and especially of his beloved dog. The book is a classic. One evening, Christopher announced that everyone needed to do a “project” relating to the Morris book.

This is more like it, we thought. Nurturing their creativity is always a good thing. Bring it on.

Christopher said he believed he would do a chalk sketch of Skip. Gosh, that doesn’t sound like much of a project. What are the other kids doing? It turned out some were doing watercolor illustrations, or sculpting clay models of young Willie or Skip. A number of the projects seemed to involve colored construction paper, although it was unclear exactly how.

Honey, you know that application to Harvard. I don’t think we’re going to be needing it right away.

Here is where being a journalist comes in handy now and then. I slipped into our den, went online and learned that Willie Morris was alive and living in Jackson, Mississippi. I called information and not surprisingly, he had an unlisted telephone number. Then, I called the Jackson newspaper, asked for their book editor, and introduced myself. Fellow journalist, Reuters, need to reach Willie Morris, and could he possibly give me the number? He did. Southern hospitality.

I returned to the kitchen, where my wife and son were still discussing project alternatives that might be a little more challenging and could possibly take more than four and a half minutes to complete. I cleared my throat and waved a slip of paper.

“Ahem, I happen to have Willie Morris’ unlisted home number here. What would you think about asking him for an interview?”

“Really? Willie Morris? Would he do that?”

“That’s the thing about interviews,” I said. “You never know unless you ask. Would you like me to call and set it up?”

“No way! It’s my project!”

I was relieved to hear him say that. I figured that in procuring the telephone number I was using a special parental skill, which I thought was acceptable. If I took it that extra step by calling the man myself, I would be crossing the line. I would just be some doofus doing his kid’s homework.

Christopher’s two journalist parents then briefed the hell out of him. We told him to tell Willie he would keep it to 10 minutes and would do the interview any time it was convenient. We had him make a list of good questions, with the best ones first, and we drummed it into his head that he had to listen to the answers and be prepared to think of follow-ups on the spot.

Then, we left the room and hoped for the best. We could hear his muffled little voice through the kitchen door. Five minutes turned to 10, then 15, then 20, before he emerged, grinning.

“I just interviewed Willie Morris!”

That’s great, we said, but now for the other part. You need to get that down on paper, so your readers can share the experience you just had. That’s what it’s about. To this day, Christopher remembers Willie’s soft Southern accent, and that he was nice enough to ask about our own dog, Barnum. Willie had even given Christopher his home address and said he would like to see a copy of his story when it was finished.

There was some very nice stuff in his notes, and he had gone off-list with new questions when it was appropriate. It was, by any standard, a good interview, and it turned into a fine story that would earn an A grade. Christopher got to go to sleep that night smugly knowing that he would waltz into school the next morning with an unbeatable project, and he hadn’t even needed construction paper.

A few days later, I asked Christopher if he had sent a copy to Willie. No, he knew just how he wanted to do this. There needed to be a nice thank-you note, some photos of Barnum and a few other things. But he had gotten a big brown envelope and written Willie’s name on it, so he was off to a good start.

Over the ensuing weeks and months and, yes, years, the brown envelope worked its way into the gaping maw that was our son’s desktop. Occasionally, it would surface for air, but then it would disappear again. The chore of preparing it for the mail grew increasingly complicated. We now had a second dog, a goofy black rescue named Luke, and a rescued tuxedo cat named Jackson. Willie would want to see them, too.

Then, of course, there was school, and Christopher was much too busy to worry about keeping a promise he had made two years earlier to a generous literary icon. Who even knew whether that sticky stuff for sealing the envelope flap was still good, anyhow?

Early in August, 1999, I stuck my head inside our teenager’s slovenly room to let him know Willie Morris had died. I knew what he was thinking, and he knew that I knew, so extra words weren’t necessary.

Later that day, he told me he was going to find the envelope and tack it to his bulletin board as a reminder not to put things off. If he actually did that, I never saw it. My take on it was that he had put off hanging up a reminder telling him not to put things off.

I understood. Nobody wants to be hectored and pestered by the past. Especially not a writer.

I should print those photos I promised to send my friend Fabio who’s almost 80…😔

And here we learn the true meaning of the word deadline....