“Hey, Bob, I just saw a story you wrote. It was in one of those tabloids they sell at the supermarket.”

“What? With my byline on it?”

“Yes, I didn’t have time to finish reading it because the line was moving. Bob? Bob? Help! Bob’s face is melting right off his skull!”

Those recent revelations in the Donald Trump hush money trial, about The National Enquirer buying stories that might have been embarrassing to Trump, and then burying them, brought back some sweet memories for me.

It was the late ‘70s, and I was working at an evening newspaper in Albany. I had a front-page column where I interviewed interesting people.

One time, I took the train down to New York City to interview the famous chef James Beard at his home. When my friends heard I had done that, they all asked the exact same question: What did he cook for me?

Absolutely nothing.

I mean, I was there in his co-op, at lunchtime, and James Beard could not be bothered to open a bag of Cool Ranch Doritos and a can of bean dip to offer me.

Nonetheless, he gave a very good interview, and I was a storyteller, so that was enough to make me happy.

Those were the days. I was young, I had bills to pay, and I was looking for ways to boost my income because my wife had just gone back to college. I didn’t know much about the economics of journalism, but I was about to learn.

There was this weekly nationwide newspaper called The National Observer, which was very respected by its really smart readership. Every issue featured a well-written personality profile that filled most of the back page, and for an unknown journalist like me, that spot dangled instant prestige.

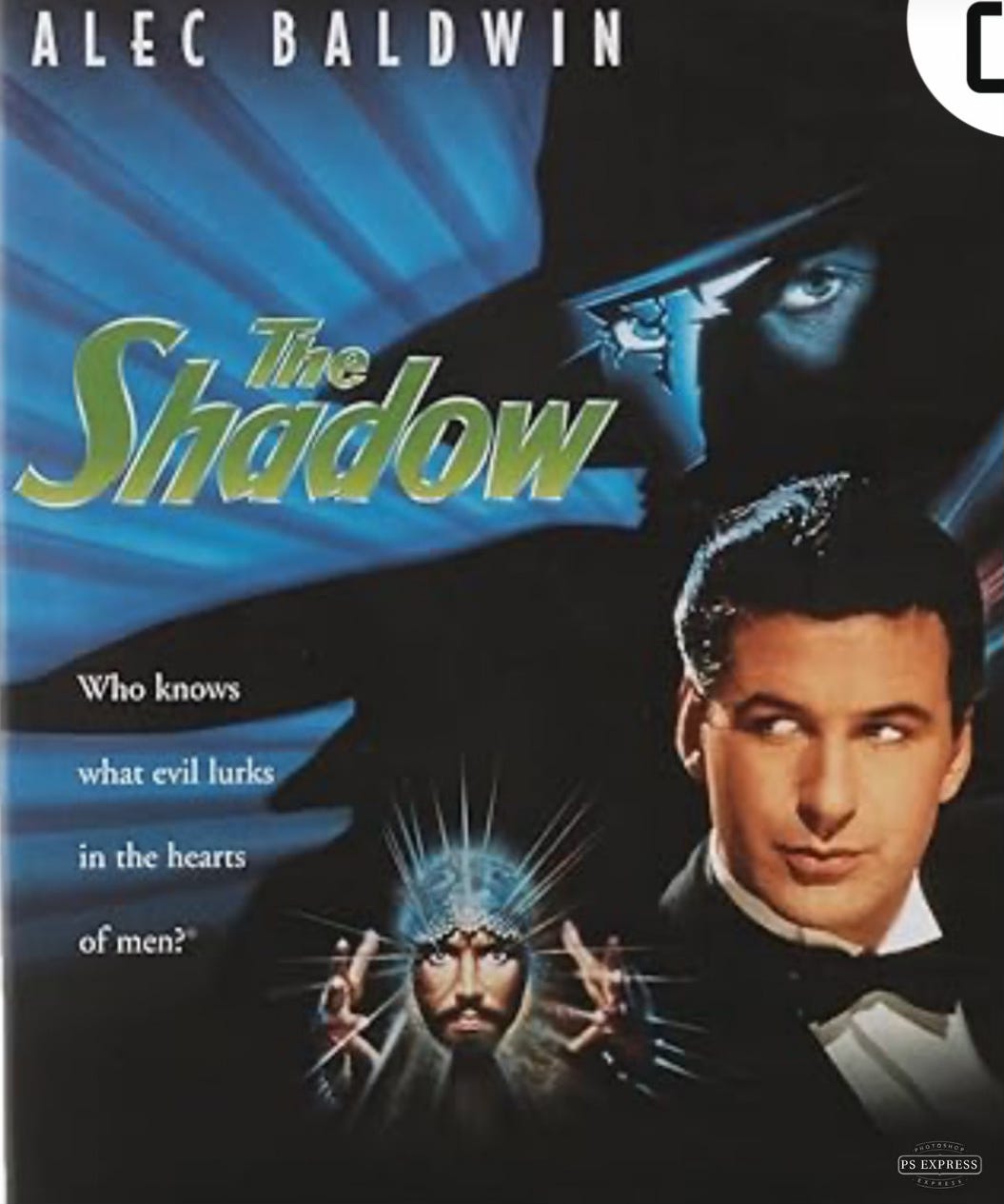

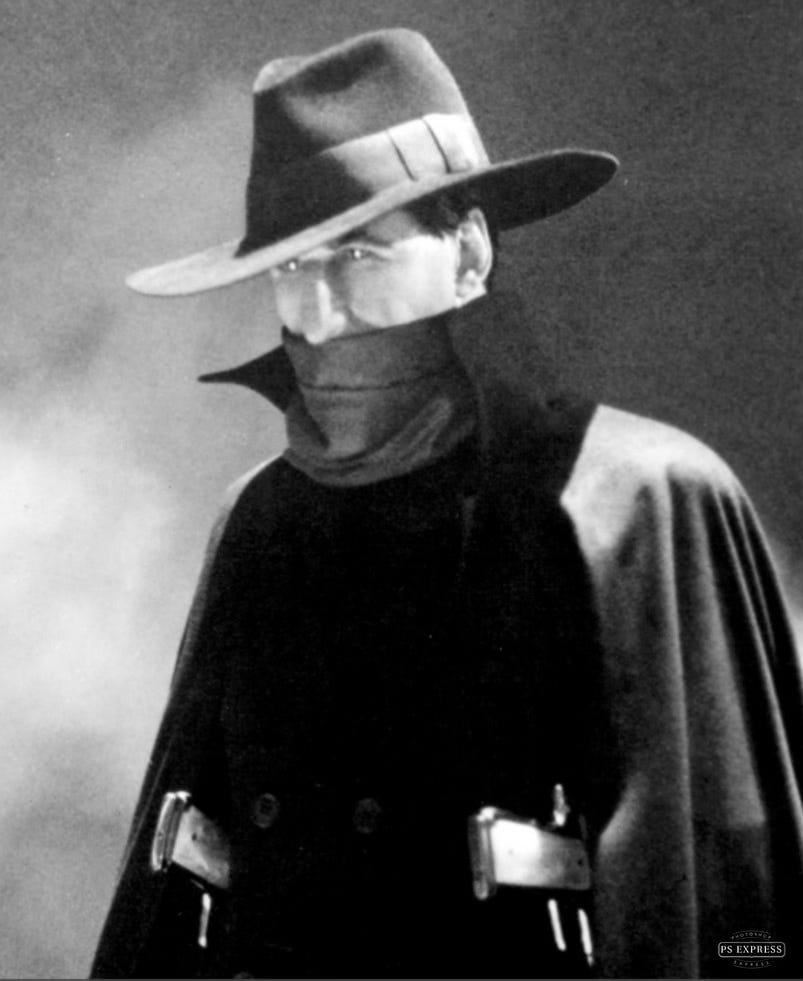

I wanted to write a story for that page more than anything. I watched for an opportunity, and I pounced. I interviewed a guy named Walter Gibson, who had been the creator of The Shadow, in the heyday of pulp fiction magazines and radio serials.

The character’s tag line was iconic: “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows…”

While America was struggling through a crippling depression, Walter Gibson was living it up at Manhattan’s famed Hotel des Artistes, churning out Shadow tales using the nom de plume Maxwell Grant, as fast as he could type. The Shadow endured, and even became a 1994 movie starring Alec Baldwin.

After I interviewed Gibson for the Albany paper, I pitched a story on him to an editor at the Observer. Just a few days later, he called and said I had earned the coveted back page feature slot.

I was giddy. This was the big time.

The Observer paid me $150 for my story, which today would be about $775. I was on my way up. Watch out, world.

Here is where the story gets interesting, in case you were wondering whether that was ever going to happen.

I got an unsolicited call from The National Enquirer, the tabloid newspaper that writes about Elvis still being alive and aliens abducting Henry Winkler. They liked my Observer story and wanted to buy the rights to reprint it.

This was sort of a dilemma. As a serious journalist I had no interest in appearing in their rag, but my research showed me they wouldn’t run it, anyway.

Its editors bought more stories than they could possibly use, so that they could print only what they considered the best of the best. The rest would end up on the spike, as we used to say.

The Enquirer was known for their generous kill fees – money they paid to writers even if they didn’t print their story. Sure enough, a week later, the Enquirer guy called me back and said sorry, they didn’t have room for my story, but my $300 kill fee was in the mail.

Hold the phone, Toblerone! The Enquirer was going to pay me TWICE as much money to NOT use my story as the Observer had paid to USE it?

I took a step back and admired the breathtaking math. My Albany newspaper had paid me to interview Gibson and write a story about him. Then, the Observer had paid me $150 for a rewrite of it, followed by the Enquirer’s check for $300, all for the same work!

I was triple dipping!

Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? It turns out, the National Enquirer knew. They told me they would love to have some more of my stories.

This seemed like an opportunity too good to be true. All I needed was to keep finding that exact sweet spot, where the Enquirer would buy my stories, spike them and send me a check, anyway.

If this sounds vaguely familiar, maybe you’ve seen a movie called “The Producers,” in which Gene Wilder realizes he can con people into investing huge amounts in a play, so long as it was a total flop, and he wouldn’t need to repay them.

Here I was, experiencing a “Producers” moment in real life.

It was a sweet scheme, quasi-legal in most states, until I got undone by a guy named Roger Tubby.

It happened that in the late 1970s there was a great deal of popular interest in former President Harry Truman, as an antidote to the sour taste the Watergate scandal had left.

This Roger Tubby guy had been Harry Truman’s press secretary, many years ago. He had some good personal yarns about his old boss, and I was happy to write about them.

Let’s see:

1. Interview Roger Tubby, run the story in my Albany newspaper column, check.

2. Sell Roger Tubby story to the National Observer for the back page spot, check.

3. Sell the story to the Enquirer, take my kill fee, and… WTF! They didn’t kill it? They used it? With a Robert Basler byline! And I had to learn that from friends who had already seen it in print!

Suddenly, every doofus waiting to buy a bag of pork rinds and a tube of Blistex was seeing my Enquirer byline at the Price Chopper checkout line!

It was a tough lesson. I was mortified, but it all worked out okay. Just a few months later, I was living in New York City and happily working for Reuters, at the start of a 30-year career with them.

I never, ever, sold another story to the tabloids, not even when I found Elvis living in my toolshed.

Crazy! And they didn't change it at all, to, you know, make it more Enquirer-like?

Bob, you had me at "what did James Beard,...", though the unwinding if this story about a story kept me rapt attentively right through the lesson learned part. Bravo as always and keep 'em coming, please!