Pie in the Sky was the Icing on the Cake

Bob Gets Some Poetic Justice...

We’re hurtling down the tracks in the London Underground, bound for Hampstead Heath. My wife, our three-year-old son and our friend. My wife and the friend write for the New York Times, and I’m a Reuters journalist, so, you know, we’re word people. Storytellers, you could say. The discussion turns to making children laugh, and who can do it and who can’t.

Our friend tells Christopher a very corny dad joke which he then has to explain. Polite smile. Then, Barbara takes her turn with some kind of riddle. The result is a giggle. I lean over and whisper in Christopher’s ear, some convoluted story about a toilet overflowing and everybody running to get out of the way and so on, and he is on the floor, laughing like a lunatic.

There is only one thing guaranteed to work on a three-year-old boy, and that’s inappropriate potty humor. I should not have to explain this to you, people.

The reason I begin with this anecdote is, I learned early on in parenting that my super-power was making children laugh. I may not have prepared Christopher to be an NFL quarterback or a NASA astronaut, but my boy can be sarcastic with the very best of them, and he finds humor anywhere and everywhere.

When we first moved to Hong Kong with a small child, we were thrilled to imagine that he would soak up all things international, hanging out with classmates from India, Taiwan, Singapore, sampling their native cuisines, learning phrases in Mandarin and Cantonese, exploring the narrow hutongs in old Beijing.

But at the same time, we also wanted to ground him in the culture of his own country. We did that by exposing him to American movies, television, music and books, all of which are readily available anywhere in the world. In addition, I began writing him poetry, usually personalized around his own experiences. I wanted him to see that language - no matter which one we speak - is a tool all of us get to use in this life.

Christopher would tell us something that happened on the playground, and the next night it was fed right back at him in a poem at story time. They started simply enough, fantasies for a young lad grappling with the mysteries of learning to tell time:

If I had a cat, or something like that,

I would teach him to tell me the time

I would say to my pet, is it ten o’clock yet?

And he’d say, it’s a quarter past nine!

As the years passed, the poems grew more sophisticated, the vocabulary richer, and come evening, it was a toss-up whether he would ask me to read him Roald Dahl, Maurice Sendak or some of my own poems. Let me tell you, that is some intimidating competition.

My poems danced from place to place in the world and enshrined countless experiences, both important and trivial. Almost always, somebody was doing something messy, something forbidden, something that could lead to nothing but trouble. Without fail, whatever was happening got worse as the poem progressed, until whatever happened in the cataclysmic last verse made the first verse seem tame by comparison.

Indeed, there was even one poem titled with that universal cover-your-ass line, “Kids, Don’t Try this at Home.”

Seeing whether frozen corn

Will melt inside your flugelhorn

Tying up your daddy’s boss

With miles and miles of dental floss

The theme of this disgusting poem

Is kids, don’t try this stuff at home!

Stop. I know exactly what you’re thinking. You’re judging me. You think I was creating a juvenile delinquent, handing him an actual roadmap for bad behavior. I wasn’t. There was never any problem distinguishing between imaginary shenanigans and the real world, not in our house.

When we went to Singapore on vacation and Christopher had a meal with an orangutan at the zoo, this resulted:

Only me, among my gang,

Has met a live orangutan

One pleasant Wednesday, we had brunch

She didn’t know, she called it lunch

When we bought Christopher a bunk bed, we soon noticed his bedroom seemed to be tidier than it used to be, and we discovered that he was “cleaning” it by simply tossing everything into the top bunk. My response was a poem about a kid whose increasingly sagging upper bunk leads to catastrophe.

“What a plan,” young Daniel thought,

“The room looks clean – it’s really NOT

“This upper bunk is big enough

“To hold a year’s supply of stuff!”

When Christopher innocently asked me once where all the giants and witches and ogres from fairytales lived, I loved the question. I told him they all lived together in a place called “Nastytown,” and then I created a book-length epic about this awful place which was, nonetheless, their home. A sampling:

In Nastytown, one local freak,

Considered to be, oh, so chic

Has seaweed hanging from her lips

And diamond-studded fingertips

She’s Molly Mischief, Nasty Mayor

Uses jam to mousse her hair

She’s got beauty, she’s got brains,

She also drags a lot of chainsMolly has some dreams of glory,

Hopes to star in her own story

No one has the nerve to tell her

She’s not much like Cinderella

One time, back home in the States on our annual home leave, Christopher was intrigued by an “All You Can Eat Buffet” sign on a restaurant. It was the first one he had ever seen. So, I created the “Buffet Family,” the gluttonous scourge of restaurant owners everywhere:

Give us some T-bones, give us some ribs!

Give us some lobster but not any bibs

Me and my family say, bon appetit,

All that we want is all we can eat!

While most of my poems were humorous, they didn’t have to be. On a visit to the dense, impossibly remote jungles of Malaysia’s Cameron Highlands, we visited the overgrown compound where a real person, Thai silk magnate Jim Thompson, was staying when he disappeared in 1967. He was never found. Theories about what happened to him ranged from tigers to Malay Communists to the CIA, and I was inspired to write, “The King of Silk.”

Malaysian hills, where orchids grow,

Around a jungle bungalow

And rugged pathways climb and twist,

A rich man vanished in the mist

This went on for several years. It was our own private thing, or at least it was supposed to be. One day, I got a call from Christopher’s third grade teacher, saying he had been reciting poems in front of the class and telling people his father wrote them. Was this true, she asked? Um, maybe, I said, playing it cagey.

I was taken aback, because this meant the little guy had been memorizing them all along and I didn’t have a clue. I asked if there would be a problem, if, just hypothetically, I had actually written those poems, and she said no. But the pupils in other classes wanted to hear them, too, and could I please send in some copies so that my son didn’t have to traverse the corridors like some wandering minstrel. My printer worked overtime that evening.

Christmas, 1992, our sixth year in Hong Kong. My mother, in Louisville, sent Christopher a cassette of children’s songs by a local Kentucky entertainer named Karen Dean. It turned out, Karen shared my super-power of making children laugh. Her gift was even more alluring, because she not only wrote songs, but she also had a band and she performed at birthday parties and other events. She was the real deal.

Christopher adored her songs, and we belted them out at the top of our lungs as we zig-zagged around Hong Kong’s mountain roads, high above the roiling South China Sea. One evening, I explained to Christopher that he should write a fan letter to Karen, telling her how much he and his friends, halfway around the world from from Louisville, liked her music. So that’s what he did, and he also asked where he could find her concert schedule, so maybe he could come see her in person the next time we came to Louisville.

Two weeks later, there was a return note from Karen, saying his letter had made her run outside and dance for joy in the fresh snow. She gave us her telephone number and said not to worry about her schedule. When we came to town, he would get a private concert in her home. This naturally became the only topic of conversation in our home for the next five months.

Karen was every bit as good as her word. We spent 90 minutes in her quirky, funky, novelty shop of a living room, with a full-size replica human skeleton in one chair - at least, I hope it was a replica - and a large green wooden pickle hanging from the ceiling. She taught Christopher to harmonize, and at random times she would point to him and demand that he invent a spontaneous verse. For my son, it was an afternoon of pure bliss, joy beyond words, something he would never forget. She was singing only for him, and he was singing only for her.

When the concert was over, as Karen walked us to our car, Christopher looked up and casually said, “My daddy writes poems. Funny ones, for me.” Karen instantly perked up and said she would like to see some. Under any other circumstances I would have thought she was just being polite, but something about her seemed very sincere. I sent her several poems when we returned to Asia, and she asked for more. She told me she was doing a pilot for a children’s television show and asked if she could put “Buffet Family,” to music and use it.

When a videotape of the pilot arrived, those insatiable Buffets were the centerpiece of the show. She had turned my poem into a tango, and the obnoxious family sang and danced and ate their way through a silly prop restaurant. This time, I was the one feeling the bliss. Why on earth had I just been writing poems when songs were so much more fun?

In the fall of 1994, we moved back to the States and my communications with Karen became easier. We decided to do a collaboration. Karen chose ten of my poems and put them to music. Because the conversion from poem to song isn’t as simple as you might think, we had to come up with choruses, refrains and harmony and stuff. Some needed to be longer, others shorter.

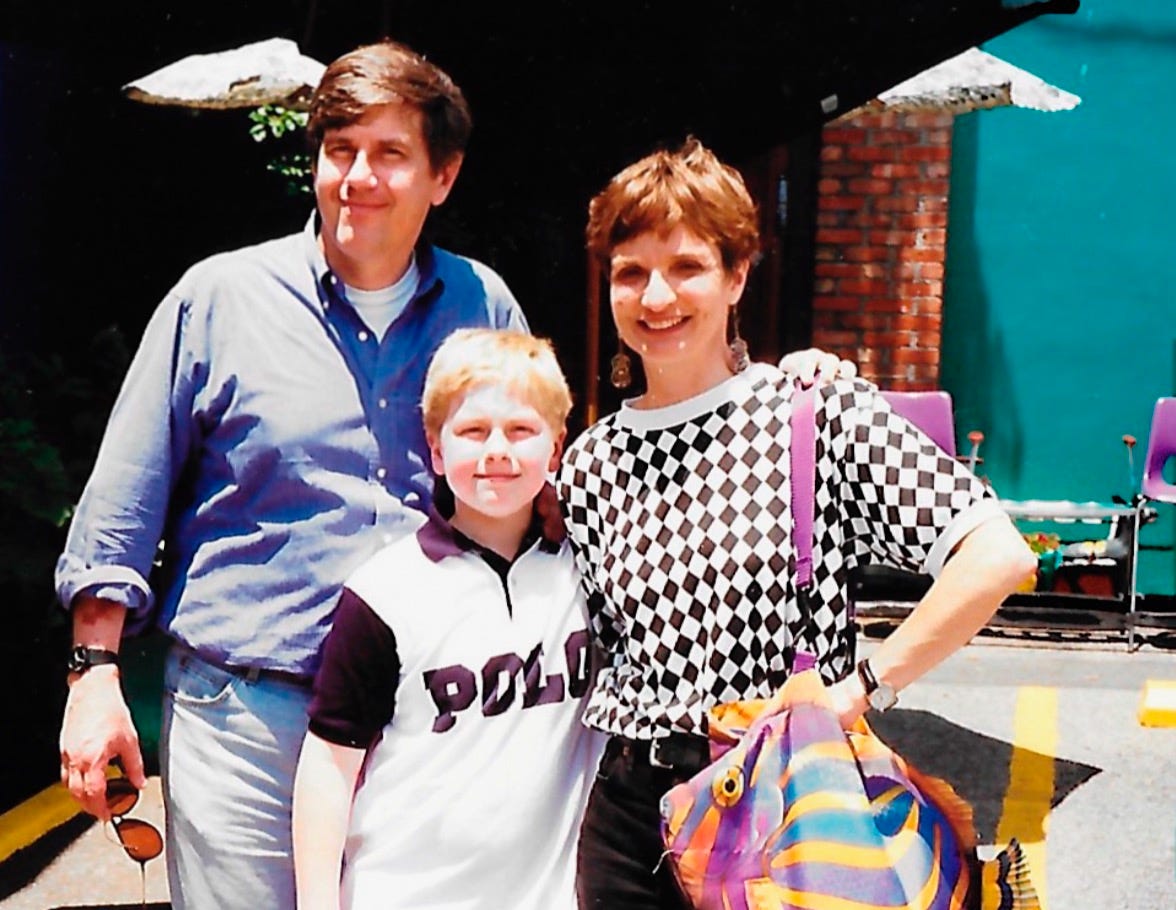

One crisp, autumn Monday in November, 1995, Christopher, Karen and I marched into the honeycombed RamCat Recording Studio in Louisville along with Karen’s husband on piano, her daughters singing harmony, and a guitar, five-string banjo and mandolin, all played by a former member of the bluegrass group, “The Dillards.” We brought in a guy who made incredible jungle sounds for “The King of Silk.” There was also a wandering blue-eyed dog.

We made rude, rousing and raucous music. Christopher provided a small child’s voice on several of the songs – it wasn’t much of a stretch for him. We took our meals two doors down at Lynn’s Paradise Café. We were our own miniature Tin Pan Alley.

On the day we were set to record “Kids, Don’t Try This at Home,” there was a small crisis. Karen decided that a couple of lines in one verse went just a little too far, and she asked me to replace them. The singer felt that some parents might not thank us for encouraging their precious children to hang on a ceiling fan and go for a spin.

I had no ideas, and the clock was ticking. The mandolin was being tuned and re-tuned. The blue-eyed dog was pacing. Suddenly, inspiration hit me like a Looney Tunes Acme Anvil. The offending ceiling fan lines were replaced with:

Gargling with Listerine,

So, you can sing like Karen Dean

The change was an instant hit in the studio, and we were back in the music-making business. Breakfast burritos for everyone, at Lynn’s Paradise Café! Even for the blue-eyed dog!

Our resulting CD, “Pie in the Sky,” came out in 1996, enjoying modest sales – at least enough to pay for the musicians and the recording facilities and our tab at Lynn’s. Karen kicked off the release with a free Saturday morning concert at Louisville’s best bookstore, to an audience of screaming little fans. Christopher and I flew in for it, got introduced and basked in the applause. The kids danced and giggled. Karen’s super-power was intact, and so was mine.

Today, some of the songs seem dated, but others hold up quite well. Every couple of years I give it a listen in my car – it’s now even available on Apple Music - with nobody else around. Christopher finds it just a bit embarrassing, but I think it means more to him than he likes to admit. I hope so.

Oh. And today, he works using words as his tools. He writes stories for a living, for television and the movies, in Hollywood.

My parents dabbled in Catholicism when I was a youth and sometimes, my dad would say a "prayer" of his own creation like: Bless this dish, bless this fish, bless this woman I hope to kish...you get it. Of course this always made me laugh and as I grew up I grew into his sense of humor and began my own blessings at the table.

Thank you for reminding me.

I am on the edge of grandparenthood, so this should come in handy….