(Me, left, Imelda Marcos, right)

Someone once said of my job in Hong Kong, “All those journalists out there have to do whatever you say, even if it’s stupid.” They had a valid point, so I tried to seem stupid no more than one or two days a week, tops. Okay, sometimes three.

As the Reuters News Editor for Asia, I was responsible for the newsfile from some two dozen reporting bureaus in 18 Asian countries. Twelve thousand miles and eight time zones spanned the boundaries of my territory. We had wars, coups, earthquakes, and financial meltdowns, sometimes all on the same day.

The only way I could begin to do my job was by trusting several hundred very savvy journalists, some of whom must at times have doubted the direction they were getting from their bosses, who were safely encased in a glass-walled office in bustling Hong Kong.

Nonetheless, I had a very nifty title, and when I visited one of our far-flung bureaus, the folks who worked in them could often parlay my stopover into an interview with a prominent government official or, even better, perhaps someone interesting.

These meetings were conducted from country to country with surprisingly similar protocols: polite introductions, a few pleasantries, and then the serving of tea or coffee and biscuits, giving way to some serious questions.

The sharing of food and drink was important because it was civilized. Sometimes the ritual was elegant, other times, not so much.

Once, during a meeting with a cabinet minister, the man told his minions it was time for the refreshments. A servant was ushered in carrying a silver tray with coffee cups, a pitcher of cream, a pot of boiling water and – wait for it – a jar of Sanka instant coffee. With some fanfare, he measured a spoonful of the dark crystals for each cup, then poured the water while a helper passed a plate of graham crackers.

The best interviews came not with officials, who after all were virtually unknown outside their own borders, but rather from larger-than-life figures, who were celebrated - or notorious - both at home and abroad.

One sweltering summer day in 1992, I sat in an airless, high-ceilinged government building in Hanoi and talked with General Võ Nguyên Giáp, his country’s revered hero of the Vietnam War. Flop sweat poured down my starched buttoned-down shirt, but I was talking to an icon, a genuine giant of world history, so I wasn’t complaining. Who else gets to do this?

Another time, I was supposed to interview famed Indian movie director Satyajit Ray at his Calcutta flat. As one of our correspondents and I walked toward his building one evening, suddenly every light went out. Total darkness, all around, punctuated only by a few random passing car headlights.

The reporter shrugged it off, saying you never knew when that was going to happen in Calcutta, or how long it would stay dark.

Using a cigarette lighter, we carefully made our way up several flights of stairs and knocked on Ray’s door. He opened it and we saw his creased and imposing face illuminated only by a candle he carried. I will never forget that sight.

Since there wasn’t even enough light in his living room to scribble notes, much less shoot photos, the three of us decided to postpone the interview until our next visit. Sadly, Ray died a few months later. He was the one who got away.

But while my meetings with Giáp and Ray were memorable – the word surreal wouldn’t be too much of a stretch – I must say they were business as usual compared with my 1992 dinner with Imelda Marcos, who was the former first lady of the Philippines and the widow of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

I believe the technical phrase for her is “a real piece of work.”

For those of you who didn’t closely follow 20th century politics in the Philippines, Ferdinand and Imelda were jointly credited by the Guinness World Records people with the largest-ever theft from a government: an estimated 5 billion to 10 billion dollars salted away. Many Americans knew Imelda as the lady with 3,000 pairs of shoes.

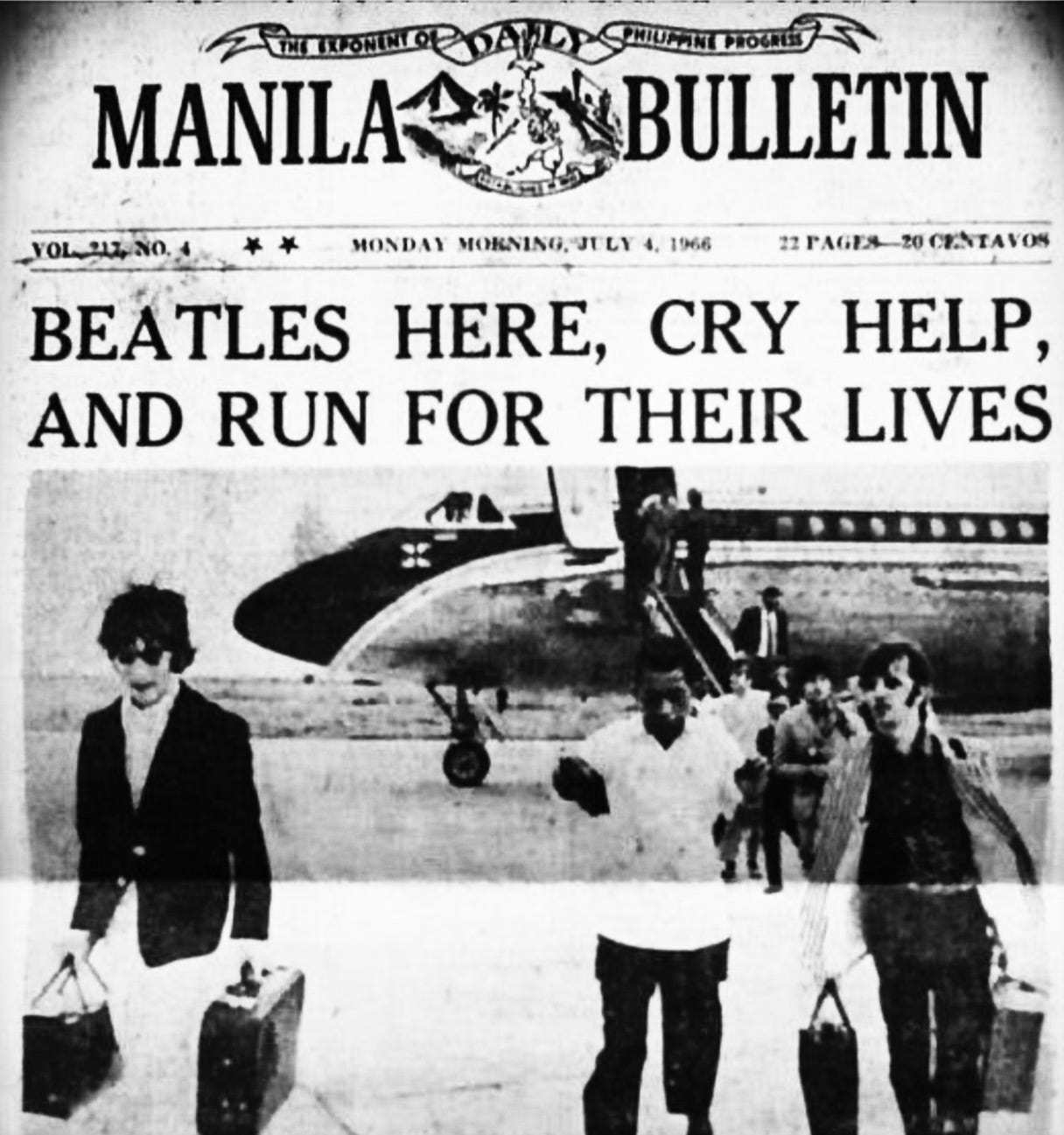

If she still doesn’t ring a bell, there’s this. In July,1966, The Beatles performed in Manila and Imelda invited them to play at a private event in the Palace. When they declined, the airport was shut down and they barely escaped with their lives.

When they landed back in London, Beatle John Lennon said they would "never go to any nuthouses again." Drummer Ringo Starr later described the ordeal as "the most frightening thing that's ever happened to me."

Our dinner was held around a secluded table at a posh restaurant. Our Manila bureau had invited her, and she brought along her son, Bongbong, her daughter, Imee, both in their 30s, and a herd of brawny security people to ensure her safety.

As those of you who do follow international news already know, Bongbong would go on to become his country’s president, in 2022.

As the visiting dignitary at the dinner, I was seated next to Imelda. There was no passion, humor, or warmth in her answers to our questions, and even her small talk seemed pre-programmed.

Every time there was a lull in the conversation, Imelda would ask me if my family was with me in Manila. Three different times, I informed her honestly that they were not.

For my part, I will admit I was fascinated by her fingernail polish, with each nail tipped with a thin white stripe. I guess I wasn’t getting out enough because I had never seen a French manicure before. Imelda assured me that it was becoming a popular trend.

So yes, there I was, discussing fingernail fashion with a woman whom Newsweek described as “one of the greediest people of all time.”

During the course of the wide-ranging conversation, Bongbong – who was Ferdinand’s only son – acknowledged for the first time that he had donated a kidney to his father, but that it didn’t take. This had never been confirmed before.

When the dinner and conversation came to an end there was cordial hand-shaking all around before her security dudes cleared a path and swept her away along with Imee and Bongbong.

Those of us from Reuters sat back down to compare notes and decide what was newsworthy from the event.

Like something from a fairytale – but not a very good fairytale – I saw in the space between Imelda’s plate and my own she had left a frilly, no doubt expensive, monogrammed handkerchief. Was this her way of leaving me a souvenir of the evening? Gallantly, I presented it to our bureau chief as a gift for his wife. I guess I’m just a very classy guy.

I was asked to write a piece about the unusual dinner for the Reuters internal company magazine, and after they printed it, I was rewarded with a scathing letter to the editor from a secretary at the company headquarters in London.

It seems she didn’t think we should be interviewing bad people such as Imelda. It was one of those reality check moments that reminded me how differently journalists see the world from other people. For the record, I would return to Manila and do it all over again, in a heartbeat.

And maybe, Imelda, this time I’ll bring my family.

Hit Parade - Most popular 5 a.m. Stories since March 20:

Did you check under the table? Maybe she left a pair of shoes. 🙂

Always interesting, Bob. Thanks for another great read.