(AI generated photo)

I was in the sixth grade. School 91, over there on Evanston Avenue. We had big old wood plank floors that amplified every sound our teachers made as they traipsed around in their high heels. At least we could always hear them coming.

Mrs. Samuels called my name and asked if I had done my homework.

“Does it look like I’ve done my homework?” I asked in my native language, which was sarcasm. I knew instantly that I had crossed a line.

Mrs. Samuels clomped slowly back to my desk. I heard every footstep. She looked me in the eyes and slapped me in the face.

That was a huge mistake. I mean, such things were allowed back then, of course, but I think Mrs. Samuels should have just stayed at her desk and used a crossbow. Quick, clean, silent. You can’t go wrong with medieval weaponry, and it was what I deserved.

I was that kind of pupil. I don’t know how my teachers even tolerated me, much less taught me anything. Every minute of every day I was either waving my hand in the air to speak, or else already flapping my gums.

God bless those teachers. That very same Mrs. Samuels was the first person to tell me I could write, and that I might want to consider doing that for a living, someday.

National Teachers’ Day is coming up in May. I like to get an early start, trolling my distant past and remembering the tiny events that shaped me. Each year I get a little closer to putting the puzzle together, and I think of someone else I should thank.

It’s almost always a teacher.

Third grade. A tough slog. That was the year they threw cursive at us, if I’m not mistaken. The only bright spot in the classroom day was story time. Miss Vogt would read to us for 20 minutes or so from some book she had carefully selected, and it began to dawn on me that there were great stories and there were lame stories, and I preferred the great ones.

This was a major step up from the lower grades, where every single book was about a boy and his dog. No girls, no cats, no exceptions. Just boys and their dogs.

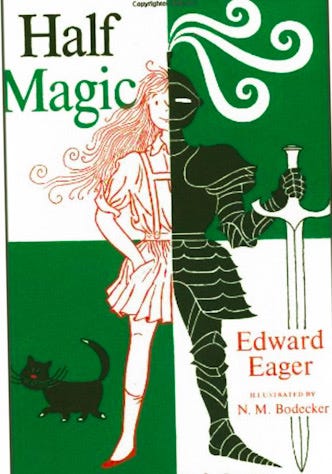

One bright day, at story time, Miss Vogt cracked open a new book called “Half Magic,” by Edward Eager, and my world changed.

What a story it was! These children find a magic coin that will grant their wishes, but only halfway. So, they have to use logic, math and clever wording to avoid only getting half of what they want, or twice what they want, or something just plain dangerous.

Fast-forward thirty-some years, and as a parent I was delighted to learn that Edward Eager’s books were still in print. I ordered all of them, and read them to my own son, in his cozy Hong Kong bedroom overlooking the South China Sea. He remembers them all, especially “Half Magic,” and he now recommends them to his friends who are new parents. And so it keeps on moving forward.

I wish I could tell Miss Vogt all the things she set in motion on that day.

Fourth grade. Mrs. Rhinehart. We had to do a report on America’s pioneers. I wrote mine in five minutes without even considering doing any research. My mom went to see her about my failing grade, and Mrs. Rhinehart patiently explained that maybe if I had gone to the library, I could have learned about Conestoga wagons and the Oregon Trail, and perhaps my report wouldn’t have sucked the way it did.

After that humiliating episode, research became my middle name. Just ask me about bituminous coal, or about West Virginia’s state flower, the Rhododendron. Good research helped propel me through a long career in journalism. Don’t bother looking for a shortcut. There isn’t one.

Fifth grade. Miss Spear. She was young, lanky and Texan. She was a former airline stewardess, back when that’s what they were called. Miss Spear taught me that good esoterica could always draw a crowd.

I listened, spellbound, as she told us about Lady Macbeth trying to wash blood off her hands, about how alcoholics couldn’t tolerate even one drink, and about how to cheat the phone company by making free long-distance calls. If you know something interesting and you can pull it out of your pocket at the right time, you’re golden.

Eighth grade. Social Studies. This was the stuff that fell through the cracks in the earlier grades, when they just showed us pictures of cheerful Indians feeding Thanksgiving dinner to sanctimonious pilgrims with big buckles on their hats.

Mr. Brunso introduced us to the horrors of slavery, the Holocaust, the violent history of the labor movement, and the Scopes Trial.

He sugar-coated nothing. Mr. Brunso wouldn’t last five minutes in red state classrooms today, and that’s a crime.

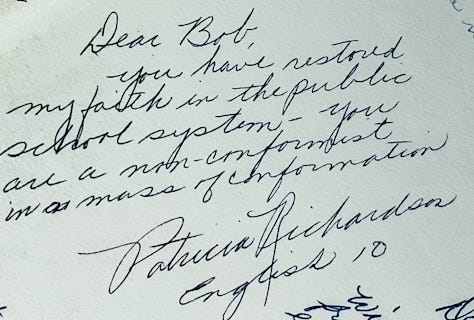

And then, there was high school English. Patricia Richardson. The best teacher I ever had. Mrs. Richardson lived in an unfair world of personal pain, but good Lord, could that woman connect with her students.

She was beautiful, smart-mouthed and funny. From my warped perspective as a 17-year-old boy, she also had long, shapely legs that stretched from here to Muncie. Mrs. Richardson was a political conservative, but I guess nobody is perfect.

Her first husband and small baby had been killed in a car crash. She had remarried, and she told us what she knew about choosing a life partner.

“Marry someone who is your best friend,” she told the class. “There will be a lot of long, cold evenings in your life, and you’re going to want to talk.”

For Mrs. Richardson, the burden of life just kept getting heavier. In 1975, she was diagnosed with cancer and given six months to live. She and her husband moved to Beanblossom, Indiana, to spend her few remaining days helping animals.

Twelve years later she was still very much alive, still helping animals. I know this because I read about her in a 1987 newspaper story.

Good old newspapers. How would we get along without them?

I wish I had told Mrs. Richardson I thought she was the best. I did take her advice about marrying a best friend, and it got me through those long, cold evenings she warned us about.

Six decades after graduation, I am still moved by what she wrote in my yearbook:

In case you were wondering, I guess this story has been about what great teaching looks like from one boy’s perspective. This is its enduring legacy.

THE NOTE though!!!!! That alone is worth THOUSANDS of $5 fees, in my humble opinion. I hope you have it in a gold frame on a wall somewhere so the Baroness can read it every time she haunts your house. ALL of these stories of what makes a great teacher are wonderful, Bob, and SO incredibly timely as the forces of evil once again try to turn our public schools into corporations. THANKS, Dear Bob, for writing THIS one especially!!! AND "for being a non-conformist in a mass of conformation." WOW.

Love this one. And, yes, as a colleague who shared an office with you, I can attest to the fact that your native language is sarcasm.