(James Taylor, singing his redundant lyrics)

Please calm down. I am not having a stroke. I just inserted some errors into my headline on purpose, to show how quickly people can completely lose it over language. Of course, they can lose it over pretty much anything these days, so why should grammar be any different?

If you don’t have an opinion on the Oxford comma, you’d better get one. Google just now turned up thirteen million references on the Oxford comma in less than half a second.

If you want to know my own feelings on the subject, you may ask my chimney sweep, my haberdasher and my ornithologist.

I was 20 years old and my promotion to cub reporter was still deliciously fresh, when several of my colleagues at the Indianapolis News invited me to join their regular Friday lunch. Burgers, beer and snarky fellowship. I wasn’t even old enough to drink, but this place didn’t care about that. I had arrived in heaven.

On the way to the restaurant, there was this snippet of conversation:

“Mike, can you loan me a couple of bucks for lunch?”

“No, but I can lend you a couple of bucks. Loan is a noun, not a verb.”

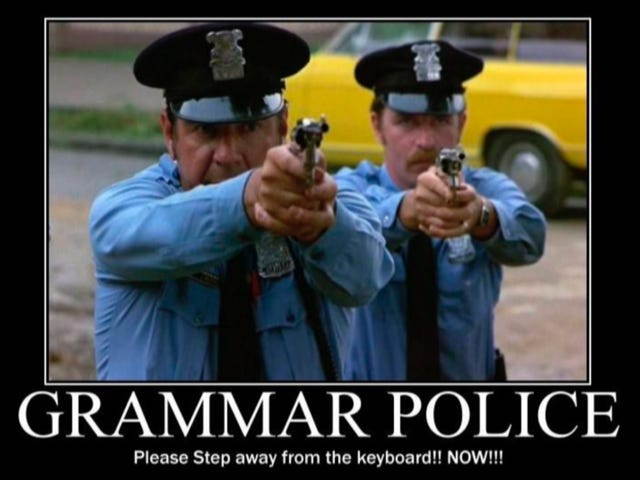

Oh, man! Smart guys being really smart! It was my introduction to what we now call the Grammar Police. Back then, we only called these folks pedants. What did we know?

Journalism, my lifelong profession, nurtures these types. Nit-pickers extraordinaire. I have been a volunteer grammar cop myself now and then, although never full-time. I was authorized to make the odd citizen’s arrest, dragging some poor chump down to the hoosegow to book him for misusing the word “hopefully.”

Hopefully, I didn’t overdo it.

There are two varieties of Grammar Police:

1. Well-intentioned wordsmiths who cherish the English Language and simply want to do what they can to gently ensure that it stays on the right path.

2. Gasbags who learned somewhere that the words disinterested and uninterested mean different things, and that fulsome doesn’t mean what you may think. This variety of cop wants to shame abusers in the most public and humiliating way possible, and then push them off the Chrysler Building.

Every journalist has his or her own triggers. It’s in our DNA. Each reporter thinks his writing is more perfect than the guy working at the next desk. Except I just tricked you because a thing can’t be “more perfect.” It’s either perfect or it isn’t The same is true of “unique.” Nothing is “more unique” or “most unique.”

You see how many dangerous word traps there are? Welcome to my world.

If I had a dollar for every time I’ve seethed over watching a television newscaster misuse “Catch-22,” I would be able to purchase Substack and fire all the writers who have more subscribers than I do. “Catch-22,” does not mean “confusing” or anything that simple. There was a whole bestselling book about it, for Lord’s sake!

Over the years, I’ve grown numb hearing those same broadcasters say, “The protest rally will begin at 10 a.m. tomorrow morning.” No. You don’t need to add “morning” if you’ve already said 10 a.m. And by the way, you don’t need to say, “12 noon,” either. Noon is just fine by itself.

Here is how I know when I’m going off the deep end. Steam comes out of my ears upon hearing people use an annoying formulation that is spreading like poison ivy through the retail sector.

“Excuse me, where can I find the frozen lima beans?”

“Those are going to be in aisle six.”

“Really? They are going to be there? You mean, they’re not there now, but they are on their way? Okay, tell them to meet me there.

I know, you’re thinking, “WTF is wrong with you, Bob?”

Your guess is as good as mine.

Petty, petty, petty. I once saw the very erudite Dick Cavett, on a program about language, smirking over hearing people say, “I can’t seem to tie my shoe laces.”

“Why do they just want to seem to tie their shoes?” he asked, with a superior snigger. “What they really mean is, ‘I can’t tie my shoe laces.’”

The problem with defending our language is, we will always lose. Oh, we can hold the line fleetingly, but eventually they’ll roll over us with their superior numbers.

Sooner or later, every popular language abuse gets sanitized. The dictionaries will bend to the will of the torch-carrying mobs, or else the “Associated Press Stylebook” will issue a new edition in which something that used to be considered unforgivably incorrect is now accepted. The Stylebook is now in its 56th edition, if that gives you some idea how fluid our language is.

Oh, before I forget, dictionaries now let you use loan as a verb. Maybe they always did.

If you want to see my wife, who is an excellent wordsmith, hurl a chair at the wall, all you need to do is turn a noun into a verb. It’s called “verbing,” and it has become a popular sport in recent years.

“He was tasked with moving the headquarters to Krasnoyarsk.”

“The lifeguard referenced swimming with jellyfish.”

Tasked? Referenced? Are these words really necessary? No, but they have worked their way into dictionaries, meaning the bad guys won again.

When journalists tire of correcting one another in English, they may turn to another tongue. Once, when we were still working at The News, my wife opened the paper to read a story about a local parade in which the reporter referred to a spectacular float as being the “coup de résistance.” She vaulted across the room to the copy desk in a single bound, to tell them the phrase they wanted was “pièce de résistance.”

What did they do? They debated whether we really needed to correct a mistake that was, after all, just in some foreign language.

I have read that the most abused word in the English Language is “irony,” and that is probably true. If you want to learn more about what words mean or don’t mean, I recommend a hilarious opinion piece by the great George Carlin, called, “If I were in charge of the networks.” In it, Carlin offers up the definition of irony and then tosses out some examples:

“If a diabetic, on his way to buy insulin, is killed by a runaway truck, he is the victim of an accident. If the truck was delivering sugar, he is the victim of an oddly poetic coincidence. But if the truck was delivering insulin, ah! Then he is the victim of an irony.”

Here is my all-time favorite example of grumpy grammar policing. Nothing could do a better job of illustrating how petty we can be when we really try:

In 1969, the James Taylor song, “Fire and Rain,” was released. People immediately loved it, and it remains a nostalgic anthem for a whole generation. I was driving around downtown Indianapolis with a fellow reporter, in his Volkswagen Beetle, when we first heard the brand-new song on his AM radio.

The final chorus closes with, “But I always thought that I’d see you, one more time again.”

“Wow!” I said, overwhelmed by the pain and emotion the singer was putting on the line.

“That’s redundant,” my colleague snorted. “He doesn’t need to say, ‘one more time, again.’ He should just say, ‘one more time.’”

I killed this fellow and buried him at a downtown construction site, where he was never found. It was for the best.

Remind me to never speak in front of you again.

Oh, Bob. I am uphauled. You have conflabulated grammar and usage, as well as spelling and punctuation. Would you like me also to point out the vociferous errors in your text? Then I will fulsomely pillow you on every channel of social media so others may learn from your flabby example.