Dear Bob: it turns out they want to tear-gas me as part of my college fraternity hazing. Does that sound okay to you?

Dear Idiot: No, it sounds as if you’ve chosen the wrong fraternity. I suppose Phi Beta Kappa wasn’t an option for you?

The above snarky exchange is a dramatization. It is my way of saying I’ve experienced tear gas, and I don’t recommend it.

Let’s start with your standard, plain vanilla tear gas, which I got to experience in the U.S. Army. Tear Gas Day was the worst thing about spending ten weeks at Basic Training, unless you count having to perform Kitchen Police duty. Nothing was as bad as that.

First, they gave us a lecture on how bad tear gas was. Then, they put us in a small, sealed room, with masks in pouches hanging from our belts, and released gas into the room.

When our eyes began to tear up, we got to put our masks on. It was the Army’s way of proving to us that the masks really worked. Sort of like proving a bullet-proof vest works by shooting you while you’re wearing one.

Even now, when I think back on Tear Gas Day, two words come to mind: vomit and snot. You have to wonder, wasn’t there some better way to prove their point?

Time marched on, and tear gas got stronger and more effective, especially the kind they called pepper gas. Imagine if strips of duct tape were rubbed through siracha, steel wool and white-hot charcoal, and then wrapped around your neck. It’s like that.

In the summer of 1987, I was in South Korea, where a coalition of students and labor unions was trying to topple a brutal strongman regime. Reuters sent me to Seoul to help our bureau cover the rapidly unfolding events.

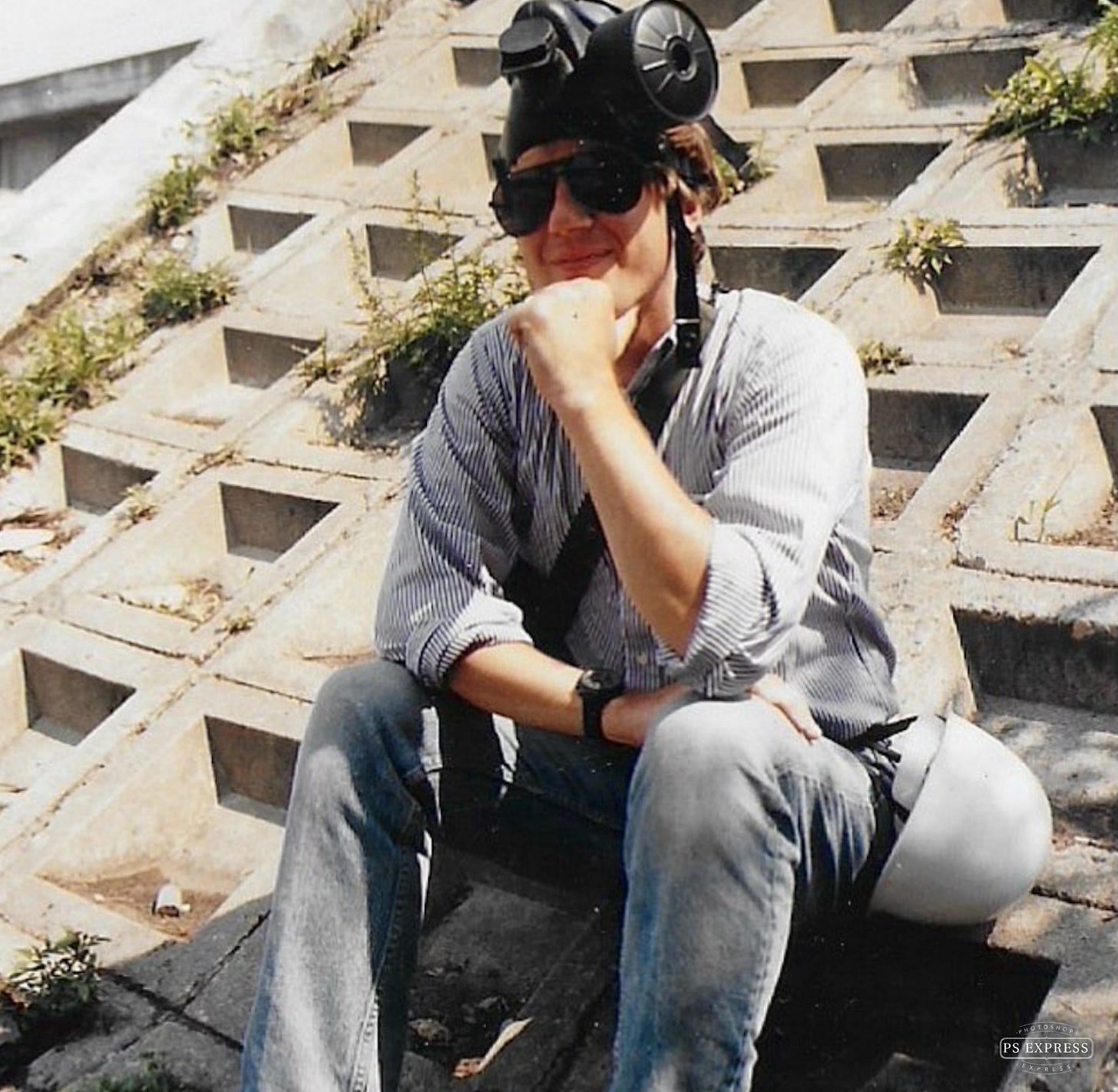

There was a rack of gas masks hanging by the door of the Reuters bureau, and we were supposed to take one with us whenever a confrontation might be a possibility. The way things were going, that was just about every day.

I loved Seoul, but it was a quirky place. One of the leaders of the opposition, Kim Dae-jung, was under house arrest and facing a death sentence, but you could call him on the phone for an interview – which I did - and get snapshots of him in his garden from a nearby vantage point. He went on to become the South Korean President and win the 2000 Nobel Peace Prize.

Maybe I just don’t get out enough, but one surprising thing about Seoul was that many barber shops did double duty as brothels. If you go to the wrong one for a trim, and you could get the surprise of your life.

I did not want to deal with this, so I just let my hair grow long. On the other hand, another visiting colleague was so delighted by this opportunity that he would ask for his living allowance in cash, each day. He was the best-groomed guy in the bureau.

During the weeks of protests, large sections of Seoul were perfectly safe, but if you found yourself squeezed in-between, say, 1,000 students shouting, “Tokje tado!” and a couple hundred riot police carrying shields and tear gas launchers, you knew what was going to happen next.

“Tokje tado,” by the way, means “down with the dictatorship.” We heard it chanted often that summer. It’s the only Korean phrase I still remember.

My first encounter with the dreaded pepper gas came at a seemingly spontaneous downtown Seoul demonstration, as a barrage of the small gray pods was fired our way. One of them hit my leg, bounced off and broke apart, releasing its contents. My gas mask helped some, but it couldn’t protect my exposed skin.

Keep in mind, the police and the journalists had gas masks, but most of the protesters had to make do with breathing through wet face cloths saturated with minty toothpaste. That worked about as well as you would expect.

If we wanted to find some action, we headed for Yonsei University, a hotbed of dissent. So much pepper gas had been used there, on so many hot summer days, that the tree branches hung heavy with the smell, and our skin began to tingle just by walking across campus.

(Hotel doorman in gas mask)

The great outdoors was a bad enough place to experience pepper gas, but indoors was even worse. One evening I returned to my downtown hotel to find that the protesters, and the teargas-firing police, had made it into the lobby in large numbers, and the air-conditioning system had helpfully distributed the gas to every room.

The resulting long night made Tear Gas Day in Basic Training seem like a fall festival country hayride. I don’t know why they can’t design a gas mask that you can sleep in.

In due course, the protests worked. On the day when it became clear the tide had turned, we wrote our stories until late into the evening, then retreated to a basement Italian restaurant near the office.

The waiters all knew us and kept bringing out food. They ate with us and cheered with us. We did “Tokje tado!” toasts with big shots of sambuca until the wee hours.

There is nothing like celebrating with people who just got their country back.

You might want to write down that phrase, “Tokje tado!” You never can tell when “down with the dictatorship” might come in handy, a little closer to home.

What an amazing career you have had. You really brought these scenes to life. Maybe you should have been a journalist. Wait. You are!

Brilliantly vivid reporting, Bob, I felt like I was actually there…… wait a minute, I was. 🤪🇰🇷🤪