Dear Readers, please do me a quick favor. Google “most Trusted Man in America.” I’ll wait.

I’m betting that what pops up is a dude named Walter Cronkite. He was the CBS Evening News anchor and was widely considered the most trusted man until he retired in the 1980s.

Times have changed. These days, nobody believes anybody. We should probably be looking for the ONLY trusted man in America, and we probably won’t find him.

By the way, you are perfectly entitled to ask why the title wasn’t most trusted PERSON. I guess the entire female population was considered kind of shifty, back then.

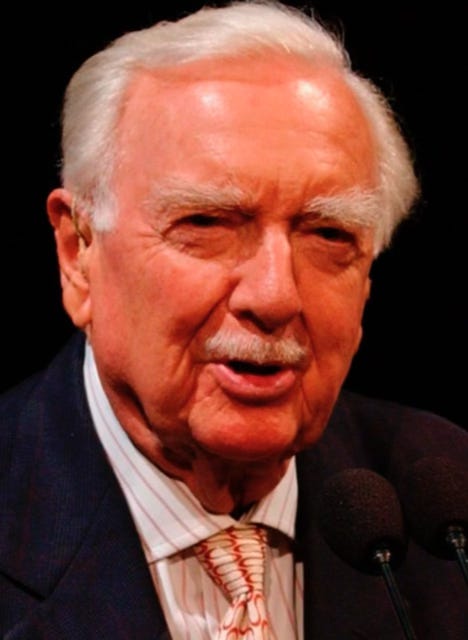

Walter Cronkite wasn’t flashy. He lacked movie star charm and boyish good looks. He wasn’t a smartass or a guy with a toothy smile and a lot of slick quips. If you looked up avuncular in the dictionary, his headshot was there.

He was Old School to the core. He ended his newscast each evening with, “And that’s the way it is,” and we damn well believed that’s the way it was.

Incidentally, on his first newscast as anchorman, he closed by telling his viewers, "Be sure to check your local newspapers tomorrow to get all the details on the headlines we are delivering to you."

The CBS executives hated that and told him to think of another catch-phrase. So he did.

In 1976, before I began a long career with Reuters, I was working for a small Albany, New York, newspaper with an unlikely name, “The Knickerbocker News.” The Knick had a solid reputation as a career springboard, a place for young journalists to get noticed.

The Knick was good, but not perfect. In 1969, the paper had been issued one of the very first press credentials for an upcoming music event being held right down the road, near Woodstock, N.Y.

You can probably guess which event.

According to a Woodstock concert retrospective written 25 years later, the “Knickerbocker News” chose not to use its credentials. The editor decided the event wasn’t worth covering, and the reporter was sent to a zoning board meeting, instead.

Wait a minute. Why am I telling two stories, one about a network anchorman and one about some dinky paper?

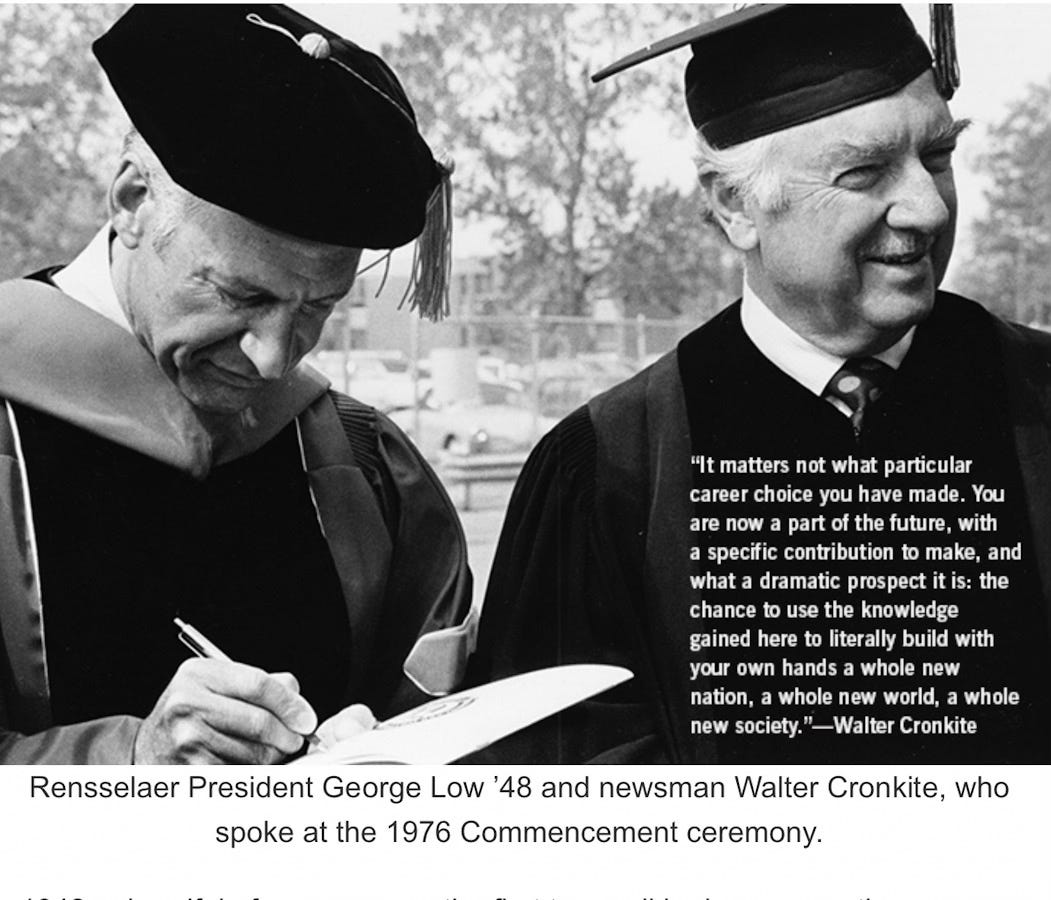

In 1976, Walter Cronkite came to our sleepy little Upstate patch, to speak at a college commencement nearby.

One of my beats at The Knick was interviewing notable people passing through the area. I was also the restaurant critic, btw, which is how things worked on a small newspaper. I could tell you where to get the best Oysters Rockefeller.

I liked the interview gig because it got me face time with people like politician Jimmy Carter, musician John Sebastian and culinary legend James Beard. It reminded me that a big-time world existed out there, and I really, really wanted to live in it.

My editor got all excited about Cronkite coming, and he ordered me to get an interview. It would be tricky because Walter wasn’t going to linger in Albany. He would arrive in a small private airplane, speak to the grads, climb right back onboard and return to New York City in time to tell his 29 million viewers, “that’s the way it is.”

That’s right. Twenty-nine million viewers.

It turned out, I did get the interview. After the speech, I was going to fly back to New York City with Walter. Sweet.

I met up with the anchorman and his wife, Betsy, in the school’s administration building after the address. I watched as a local Albany anchorman did a five-minute “exclusive” interview with Walter. I guess he meant his interview was “exclusive” except for the print reporter standing right there who was about to board a small plane with the Cronkites.

We took off smoothly and everything was fine at first. Just me, Walter, Betsy, a pilot and co-pilot. I had been expecting the sleek sort of private jet the drug dealers use in the movies, with free-flowing cocktails and swivel seats, but this wasn’t like that.

I had flown in fancier planes than this one, in the Army National Guard.

I didn’t know it yet, but my entire experience that afternoon was to be a lesson in how you act when you have quiet class, and you don’t need to prove anything to anyone.

Once we were airborne, the co-pilot came back to see if we were doing okay. Walter, who had eaten nothing since breakfast, said we were ready for our lunch.

“What lunch?” the co-pilot asked the Most Trusted Man in America.

“The school told me there would be sandwiches for us on board,” replied the famished Most Trusted Man in America.

“Here are some peanuts,” said the co-pilot, popping the vacuum top on a can of Planters.

The anchorman did not pitch a fit. He shrugged and took it totally in stride, scooping out a fistful and passing the Planters can to Betsy and me.

While I was disappointed not to be flying in an airplane a drug kingpin might use, I was starting to notice the total lack of pomp. Besides, I thought, at least I would get to ride into Manhattan from the airport in Walter’s big black CBS limousine, right?

Nope. Upon landing, we walked toward a taxi line, where Walter hailed a yellow cab. Apparently, he didn’t like sleek black CBS limousines any more than he liked drug cartel jets.

The interview was fine. My story was solid, but hardly ground-breaking. I hasten to add, any deficiency was my fault, not Walter’s.

I only recall one small part of what was said, which would echo throughout my career.

Walter told me an anecdote about his days as a young reporter, in Kansas City. One day, his boss’ wife telephoned to say she had heard there was a big fire in the city.

A short time later when the boss checked, the story hadn’t been filed. He stormed over to ask Walter why not, and the reporter said, “I couldn’t confirm it, so I didn’t write it.”

That incident almost got him fired, he said, chuckling as he ended the tale.

I stupidly thought there was going to be more to the anecdote, and I asked him whether or not there really had been a fire.

“That didn’t matter,” the Most Trusted Man in America snorted. “There is a right way to do things in this business.”

I would think about that wisdom a few years later, when I had moved on up to work for Reuters. On January 20, 1981, 52 American hostages who been held captive in Iran for 444 days were finally freed and allowed to fly home.

Everyone in America had been waiting more than a year for this moment, and Walter was broadcasting live. Someone was speaking to him through an earpiece, telling him that another news outlet was reporting the hostages had actually taken off.

“I don’t care,” he snapped. “Let me know when Reuters reports it, and then we’ll put it on the air.”

So. Not to boast, but as the Most Trusted man in America had once told me, there is a right way to do things in this business, and it looked as though I had landed in a good place to practice that.

Love everything about this one. What an incredible and fortunate experience to interview this iconic TV journalist. Makes me proud, too, to have worked at the news service that Walter Cronkite trusted. Very, very cool.

When I worked at ABC Radio in the 1980s, we would often get conflicting news on the wires. Our newsroom refrain on anything international was, "Wait for Reuters." It's one of the many reasons I always wanted to work for Reuters. And that's the way it was.