I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by

-- “Sea Fever,” John Masefield

When I was a young lad of 24, I went off to sea. What I mean by that is, I married into a family of people who owned a boat and loved to sail. They were Yankee Episcopalians, and it’s what they had to do.

There are different kinds of sailing enthusiasts. My in-laws were the kind who loved to hoist sails, plot meticulous courses, tie knots and stuff like that. My wife was another kind of sailor, who prowled the deck looking for the best place to get a tan while reading a good mystery. I could see myself being that kind.

One day, as our first married summer approached, Barbara told me she had great news. We were invited to New York, to go cruising on Long Island Sound on her family’s sailboat. It would be a lot of fun, she said. Just the two of us, along with her father, whom I barely knew.

“Wow, that’s really cool! So, like, we sail out on the Sound for a couple of hours and then come back for dinner? Hell, yes!”

“No” my bride patiently explained. “We go out for a week. That’s what a cruise is – we’re in a different port every night.”

“Wait. Night? This is a sleeping deal? What if it turns out that I get really seasick? If that happens, then how long do we stay out?”

”The same. A week.” Her unspoken message seemed to be that she wouldn’t have fallen in love with a guy who got seasick.

Suddenly, I started paying closer attention to this plan. An entire week at sea? What if we got hungry? Or thirsty? Or had to go to the bathroom at some point?

Their boat, the “Different Drummer” was a sloop. Sloop is a made-up word combining sleep and poop, which are the first two things you think of when deciding whether you really want to spend a whole week on the water. It had all the right amenities, but things on a sailboat have different names than on dry land.

The kitchen is a galley, the bathroom is a head, the bed is a berth, and so on. A rope isn’t a rope, it’s a line, except some ropes are called sheets. You can look it up. The left side is called port, and the right side is starboard. You don’t go into the cabin, you go below.

If you want to make yourself understood on a boat, you need to learn a whole new language. Like Vietnamese, only more difficult.

Sloops have only one mast. If you see two masts, it’s either a yawl or a ketch, or else it’s time to slow down on the afternoon cocktails.

When you have mastered all the new words, you graduate on to sentences. The most important sailboat sentence is, “Jibe ho!” This is what they say immediately before the boom – don’t ask me what that is, but it’s big and heavy – is about to swing violently across the center line of the cockpit, possibly taking someone’s teeth with it.

In other words, your reply to “Jibe ho!” should not be, “Sorry, could you please repeat that?”

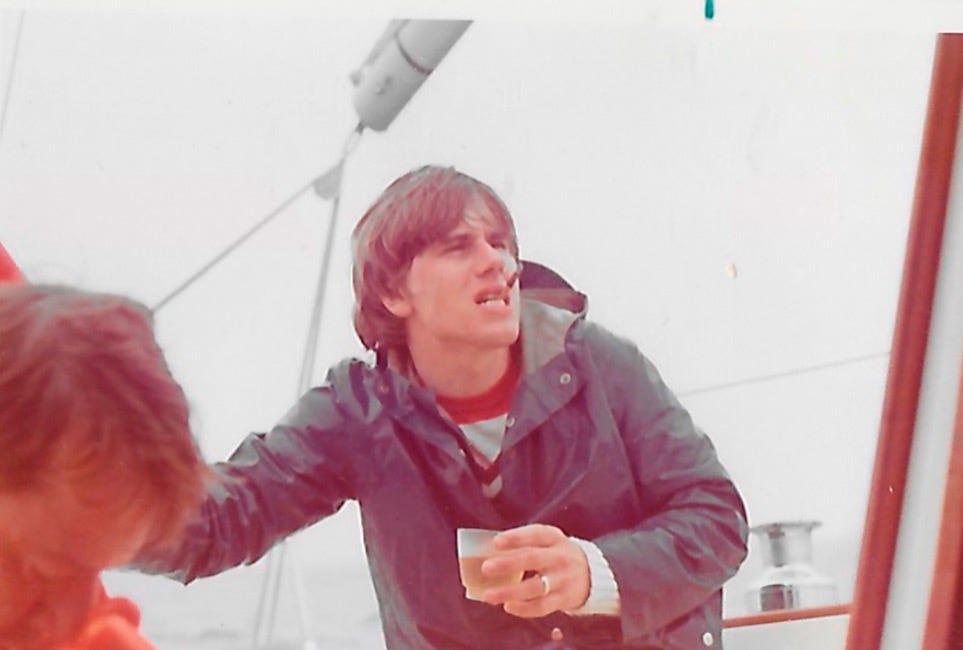

Our cruise was set to begin just after my August birthday, and Barbara’s gifts to me included something called foul-weather gear, which is what you landlubbers would call a raincoat. Except, a raincoat doesn’t add “foul-weather” to its name. Think about it. Have you ever seen a “foul-weather umbrella?”

I found myself looking forward to going out on the water, being the master of my fate, the captain of my soul, able to set sail and go anywhere we wanted to go. That is, as long as the wind and the tides wanted to go there, too. I quickly learned the most important thing on a sailboat was the tide book, which told you exactly the right minute you had to get under way.

For instance, on the very first evening of our cruise, my father-in-law, the Old Captain, showed me in the tide book that we were going to have to weigh anchor at 5:16 the next morning.

Fast-forward to 5:16 a.m. It was dark and cold and drizzling. Barbara and the Old Captain were below, enjoying steaming mugs of coffee, and I was in the cockpit, raindrops pelting my glasses so I couldn’t even read the compass.

My numb fingers were frozen to the tiller, looking all like the Gorton’s Fisherman. A slim cigar dangled from my lips, but it wouldn’t stay lit. The Old Captain stuck his head out of the cabin, wanting to make sure I was enjoying the moment as much as he was. “Who wouldn’t love this?” he asked. He disappeared below before I could tell him.

A couple of hours later, with the rain stopped and the sun shining, Barbara and the Old Captain ventured out of the cabin, all dry and smiling.

It turned out, sailing didn’t only involve learning a whole new language, it involved complicated math, as well. I was handed a detailed nautical chart – you would call it a map - and a protractor.

The Old Captain showed me where we were, exactly, because we could read the nearest buoy number with binoculars. Then, he pointed to a tiny dot on the chart, Block Island, Rhode Island, which was where we were going. I gazed in that direction and saw nothing on the horizon.

He told me I was going to plot our course, myself, and that if I did it right, in a few hours we would spot land.

“Just out of curiosity, if I get it wrong and we miss Block Island, what’s the next piece of land we come to?” I asked.

“Portugal?” he shrugged. He could be a man of few words.

Late afternoon that day found me lying prone on the bow of the boat, anxiously gripping my binoculars and bracing with my elbows. I hadn’t seen a buoy for hours. Then, very gradually, I began to make out a looming mass ahead, right where my math had said it would be. What a rush! Beautiful Block Island! Who cared that this was the smallest state? I had found it, anyway.

A couple of hours later the three of us were on dry land, in a restaurant overlooking the harbor. At tables all around us there was talk of wind and tides and unfinished journeys. Spinnakers and jibs and halyards. Sailor talk.

I was feeling a self-satisfaction bordering on cockiness. I was Ferdinand Magellan, savoring a very dry martini and oysters on the half shell. I had been safely carried to this place by a Different Drummer. I knew the world wasn’t going to get any better than this, ever.

The sailor’s life. One minute it’s foul weather gear, freezing drizzle and “jibe ho!” and the next minute it’s grog with the Old Captain and his sun-bronzed, buccaneer daughter. What a week this was going to be. For me, the morning tide couldn’t take us out soon enough.

.

What a great story

Really great! I needed that laugh. Did you actually refer to Keith as The Old Captain to his face?